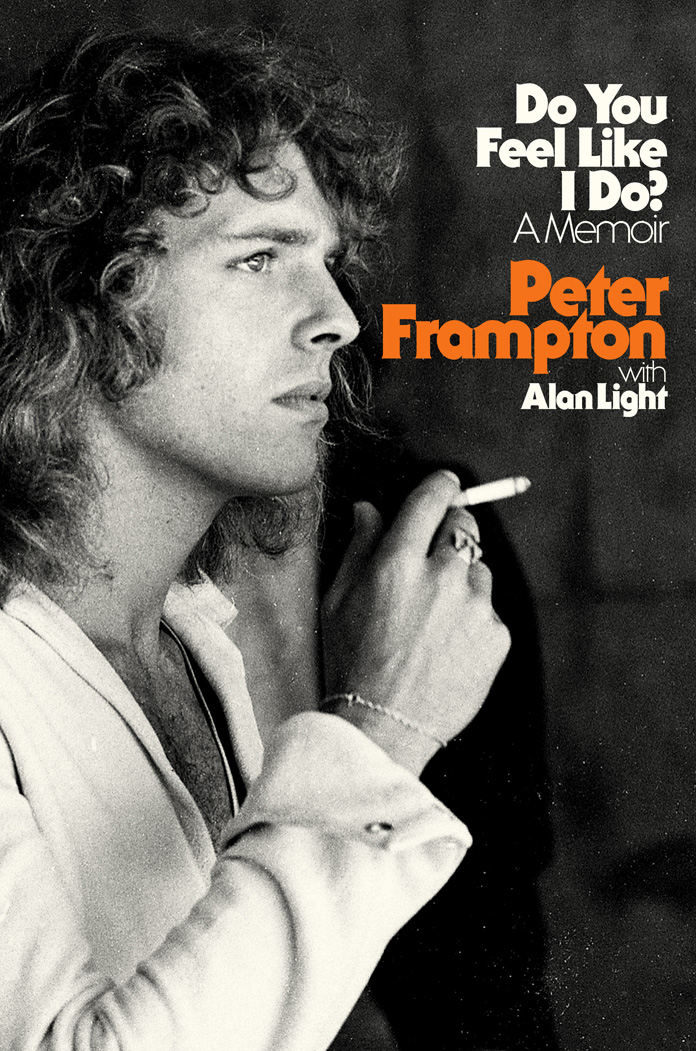

Peter Frampton on His New Memoir “Do You Feel Like I Do?”

Memories and Friends

Oct 21, 2020

Peter Frampton

![]()

Peter Frampton, who is recognized as one of the world’s greatest guitar players, has traveled the globe, earned a #1 record (Frampton Comes Alive), and was friends with David Bowie as a schoolboy. Indeed, in many ways, Frampton has lived a charmed life. But it hasn’t all been roses and sunshine for the virtuoso, as he explains in his new memoir, Do You Feel Like I Do?, out yesterday. The lengthy book, which talks about Frampton’s loving and supportive parents and his friendships with the legends of rock (from Bowie to The Beatles), also talks about his bouts with depression, his debilitating physical afflictions, divorces, and band breakups. The memoir isn’t so much a window into Frampton’s life as it is a wide-open front door and a magnifying glass. But that’s the artist’s style: put it all out there, leave nothing for later. We caught up with the musician to talk about his parents, his love of songs, his musical relationships, and much more.

Jake Uitti: Do you remember what went through your mind the first time you touched a musical instrument and was it your grandmother’s banjolele you found in your attic?

Peter Frampton: Yes. I mean, I had—she had a piano in her living room but I don’t think—I think she might have played it. I might have, like, put my hands on it. But the first time that I actually played an instrument or picked up one was the banjolele.

Do you remember what went through your mind when you were exposed to the magic and possibility of the strings?

Well, first of all, I asked my father what it was. We’d found it in the attic. We’d gone up to find our suitcases for our summer holiday and I said, “What’s this?” He said, “Oh, that’s something—an instrument grandma gave me to give to you one day. She thought maybe you’d like to play it.” So, I said, “Can you play it?” He said, “Yeah.” So, he got it out and played “Hang Down Your Head, Tom Dooley,” “Michael Row the Boat Ashore,” and “She’ll Be Coming ‘Round the Mountain.” [Laughs] And I was in awe and said, “Give me that thing!” Politely, to my father, of course. It just was—I mean, I remember still the moment of being in the attic, finding that. I remember the feeling of finding that and that was, like, I just thought, “Wow!” I became really good on it—proficient, not good—really quickly. All of a sudden it became my thing, my music. It was all-important to me at that point. It really started the whole thing, just those four gut strings. I’ve never forgotten it.

You’ve been friends and collaborated with many of the greats. Is there a commonality amongst people like Mike McCready, George Harrison, Ringo, Clapton, and Bowie that you’ve noticed beyond just a love of music?

Yeah, I think that all the people that I’ve ever met who are artistically amazing, whether it be a singer, photographer, painter, guitar player, or a keyboard player, or whatever—all of these people that have become successful—I’ve identified the same kind of passion for what they do that I have for my music. It’s something that once you find that passion for whatever you are going to start to do, I think it’s something that never leaves. Passion can fade a little bit but it always—you know, we all get fed up with something. Sometimes when I come off tour, I’ll put the guitar in the corner and I won’t look at it for a couple of days. But then, all of a sudden! It’s like, I got to play! I can’t describe—except the only word I can use is passion. Whatever it is, those people all have that same kind of passion for whatever they have chosen as an artistic output for them.

You were lifelong friends with David Bowie—or, Dave, as you knew him—from childhood. Does he still pop into your head at random moments?

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, David visited my house in Los Angeles many years ago before the album, before I recorded with him or anything like that. So, yeah. I mean, all the time.

In your new book, you talk about how all you wanted to do with your life was play guitar in a band. But why do you think your career was so much more tumultuous than that?

[Laughs] I don’t know! I think it all started by accident with me being pushed into singing in The Herd. That was my entry into something that I hadn’t planned on. Obviously, I enjoyed it. I enjoyed singing, always have. But I I’ve never really thought of myself as first and foremost a singer. It’s kind of the whole package with me. But if you ask me what I thought of myself, I’m just a guitar player. That’s what I do and all these other things are spin-offs basically, I guess, from the passion that I have for my music and my guitar. I never in a million years—I mean, when I went from The Herd where I was one of three singers, but I got chosen to sing on the singles, the big hits. Then when I formed Humble Pie with Steve Marriott, it was to get away from that because I knew that, yes, I would be one of the singers in Humble Pie but we could definitely lean on Steve Marriott to a greater degree because he’s one of the all-time greatest rock singers there ever was, you know? And we had him in our band! So, that was probably—to sing a little but mainly play guitar is my most comfortable position, The Humble Pie position. But then when I left I had to do it for me-self!

What did you enjoy about playing live and why do you think that translated to the records you released, especially 1976’s Frampton Comes Alive, which was so successful?

I know—I’m so thankful! There’s something about me when I perform that—it’s that indefinable thing that certain performers have that comes across to an audience. You appeal to them in a certain way. Whatever my appeal is, I think that it transcends visual and becomes, when you listen to the live record—I mean, I’ve always been a great live performer because I learned from the best. From Steve Marriott to every band I’ve ever played with when I was opening the bill, useless at being a front man at that point and learning step-by-step like, “Oh this works, that didn’t work, oh dear!” Then it gets to a point where the most comfortable place for me in life was on stage. There’s no inhibitions, nobody to tell you, no. You could say that to me in the studio but once I walk on that stage, no one could tell me anything or give me clues as to what to do next. It’s all got to come from me. And I built this character that is me, the performer, over the years that something that I do live transcends that you can actually feel it just by listening to the live record, I think. I make good studio records but there’s something extra that happens when I perform live and you capture that.

You’ve lived in and seen many areas of both the U.S. and the world. What does this do for you now, knowing lots of kinds of people, seeing how different places work?

First of all, being born in Europe, in England, and for the first 24 years of my life, I grew up under a European umbrella, as it were, an English umbrella of the way we live, the way we speak. Then when I was 19, I first came to American and it was the wild, wild west, as far as I was concerned. It was this place where all this music and a completely different way of living. I mean, the first place I ever came to straight from England was New York City and that’s a major change in outlook! [Laughs] I just think I had the—I was lucky enough to be brought up in Europe and see that way of life and how people react to certain things, their policies, their religion, their politics. And I’ve also been able to see around the world how other people live and how they are affected by the different ways that people are brought up.

I think that coming to America—I came to America and I am an American citizen now. But I don’t believe that any country is the “best country in the world.” And America can’t really say that now, anyway. [Laughs] But I think that America had thought a bit too much of itself when I first came here. It’s very good to be patriotic and I am very patriotic for this country and for my old country, you know? For both. If I was young enough, I’d go fight for this country, I’d go fight for England, if I had to, you know? Like my dad did. But I think that there are many countries around the world that do things in a different way than America and are better than America. America is not the best at everything. Yes, there is freedom here—questionable right now, unfortunately. But I really see—I’m really privileged to have been able to travel the world and to see the good and the bad in all countries and I think I’ve learned from that.

You’ve been diagnosed with IBM, which is a serious degenerative health affliction. You’ve also lost work in the Universal fire, experienced addiction and divorce. Yet, you remain an especially resilient person. Why?

Oh, that’s my parents. I think it’s just my upbringing. Both my parents, and my brother too, he’s the same, were very resilient. I think I was just taught that, you know, if you fall over, you brush yourself off and you get back up. And you learn you won’t fall that way again, you won’t make that mistake again. We’re always learning. I will be learning, like you will be, until the day we drop, you know? There’s always something to learn, you never know everything. And I think there’s an optimism that I got from my parents that—you know, I’ve suffered from depression, as well. I’ve run the gamut of emotions in my live, obviously. I’ve been at the top of the world, I’ve been in hell. [Laughs] But, you know, I think my failures are the things that have made me resilient because I’m basically an optimistic person. It’s like my mom and dad said, “Brush yourself off, get up, alright. And start again. It’s never too late to start again.” And that’s very true. I just think I credit them, my parents, with bringing me up. I’m very lucky to have had the parents I had—both my brother and I were.

You talk in the book about getting your famed black guitar, the “Phenix,” back again after a plane crash and not having it for decades. What was it like for you to touch that guitar again after so long?

Oh, gosh! I can remember where I’m sitting—in a living room of a suite in a hotel in Nashville and the two guys come up, the minister of tourism and the luthier that actually recognized the guitar. So, they both came from Curaçao, an island off the coast of Venezuela. And they came in the room carrying this guitar in this most awful plastic, like, shitty case. It was a cover, it was basically like a zippered plastic bag for it. And he gave it to me and I knew instantly with the weight of it, because it was a very light Les Paul. Before I even opened it, I knew it was mine. I knew from pictures, I just didn’t want to tell him because then he’d probably want six billion dollars for it. So, anyway, when I got it out of this horrible little case, I put my hands on the neck and just looked up and said, “Yeah, this is mine. This is my guitar.” It was unbelievable. Then we all cheered—there’s actually film of it on YouTube. So, we went all got in various cars—there was quite a few people there in the room—and we went straight to Gibson custom shop and had it verified as what it was. I’d never had it verified as to what it really was, you know? So, it was verified as a ’54-55 Black Beauty that had been worked on and turned into a Gibson custom with the three pickups. So, yeah, all these experts in the area were there, as well as the head of the custom shop there. It was a great day.

Last question, Peter. And that is, what do you love most about music today?

Well, music is something—I like to write it. I love to listen to a lot of different artists but the thing that still turns me on about music is that I can sit down with a guitar or sit down at the piano and I can make music. And I feel that’s a gift that I will always be thankful for. Because it’s something that whether I’m happy or sad, it’s transcendent. It just makes me feel better. It’s a healing thing. Music is very healing. You can use it to rejoice or, for me, if I’m sad or not feeling great, it’s something that will bring me out of that. It’s medicinal for me! As well as being something that I trumpet as being rejoiceful, you know? It’s all encompassing. As they say, “Music is my life!” But I say that in the broadest of terms and I’m so glad that I can still say that.

Support Under the Radar on Patreon.

Current Issue

Issue #72

Apr 19, 2024 Issue #72 - The ‘90s Issue with The Cardigans and Thurston Moore

Most Recent

- Under the Radar Announces The ’90s Issue with The Cardigans and Thurston Moore on the Covers (News) — The Cardigans, Thurston Moore, Sonic Youth, Garbage, The Cranberries, Pavement, Lisa Loeb, Supergrass, Spiritualized, Lush, Miki Berenyi, Miki Berenyi Trio, Emma Anderson, Hatchie, Ride, Slowdive, Velocity Girl, Penelope Spheeris, Terry Gilliam, Gus Van Sant, Ron Underwood, Kula Shaker, Salad, Foals, Semisonic, The Boo Radleys, Stereo MC’s, Pale Saints, Blonde Redhead, Sleater-Kinney, Cocteau Twins, Lucy Dacus, Alex Lahey, Horsegirl, Grandaddy, alt-J, Squid, The Natvral, Wolf Alice, Jess Williamson, Sunflower Bean, Orville Peck, Joel McHale

- 10 Best Songs of the Week: Fontaines D.C., Cassandra Jenkins, Loma, John Grant, and More (News) — Songs of the Week, Fontaines D.C., Cassandra Jenkins, Loma, John Grant, Good Looks, Hana Vu, Belle and Sebastian, Yannis & The Yaw, Strand of Oaks, Home Counties

- Fresh Shares New EP ‘Merch Girl’ (News) — Fresh

- Premiere: LOVECOLOR Shares New Video for “Crazy Love” (News) — LOVECOLOR

- Final Summer (Review) — Cloud Nothings

Comments

Submit your comment

There are no comments for this entry yet.