Mike Hilleary on His New Music Journalism Book “On the Record”

Taking Control

Oct 15, 2020

Photography by Wendy Lynch Redfern

Web Exclusive

![]()

It’s difficult to explain what a music journalist does to the general public. The most common response is, “You write reviews?” Which then leads to giving more and more detail about the profession, eventually resulting in the person you’re speaking to becoming further confused, and, in many cases, incredulous.

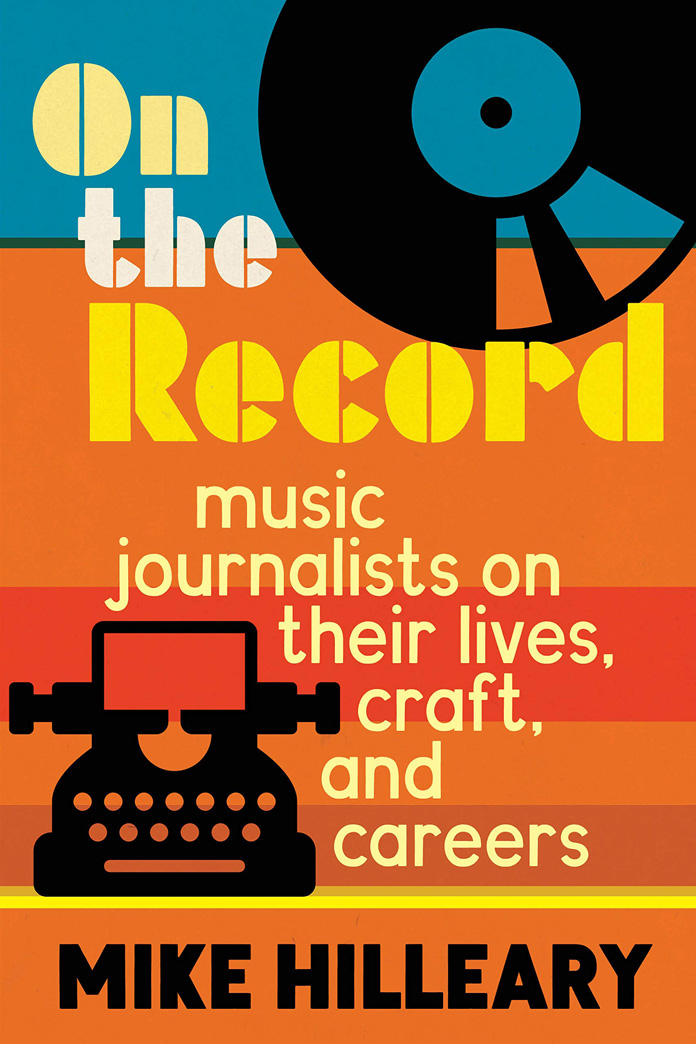

Under the Radar’s own Mike Hilleary—who has spent half of his life being a music journalist—turns the spotlight onto music journalists in his first book, On the Record: Music Journalists on Their Lives, Craft, and Careers. Hilleary himself fell into music journalism in high school when he couldn’t get into a creative writing course and was scheduled into journalism instead—which was at odds with his storytelling instincts. Joining his fellow students at the local newspaper, The Free Lance-Star in Fredericksburg, VA, he began contributing to the weekly insert, It! Magazine, entirely penned by teenagers. Mentored by the editor Dave Smalley, Hilleary discovered the world of free music, free shows, and getting to meet and speak to your favorite musicians, all in exchange for writing about them. As Hilleary says, “I enjoyed writing. I was enjoying music. It was a natural pairing of those two interests from there.”

In On the Record, Hilleary collects interviews he conducted with legendary names in the field from Rob Sheffield to Chuck Klosterman, Jessica Hopper, Pitchfork’s Puja Patel, NPR Music’s Ann Powers, Under the Radar’s publishers Mark and Wendy Redfern, and many, many more, into an oral history of sorts. Broken into chapters that dissect the early years of these music journalists, various parts of the profession from interviews to criticisms, the industry and music journalism’s place in it, On the Record places it all in the context of the changing culture over the last half century.

Lily Moayeri (Under the Radar): You mention in the introduction to the book that you started reaching out to various music journalists as a way to make connection in what is a very isolated job.

Mike Hilleary: I don’t think when I was studying journalism and was developing this enthusiasm for music and writing about it, just how it was really going to be on a day-to-day level. I had some image in my head of working in a newsroom, like that’s where it was all going to take place. But writing—any kind of writing—requires so much isolation.

Did you already have the idea for the book prior to reaching out to the music journalists or had you already made those connections and then the idea for the book came about?

The book was a serious case of wishful thinking. Finding a steady, non-freelancing job had been my goal for years. I knew what I was passionate about. I knew music journalism was something I wanted to pursue in my life, but after many years out of college it became clear that I needed a job where I could write and not feel like such a financial parasite on my wife. I applied to anything. Unfortunately, once I got through that initial screening phase, the job interviews would always turn to “So I see here you’ve done a lot of writing on music. We’re a [insert type of] company. Do you think that you translate what you’ve done in the past to this type of subject matter?” When I didn’t get the job, it was always pretty clear they didn’t think I could translate my writing ability to something other than music. I was feeling pretty depressed.

In between filling out job applications and getting rejection notices, I started thinking, “Was this the kind of thing other people go through trying make a living as music journalist?” All those writers I look up to and read, how did their experience compare to mine? It was in a very existential headspace. I didn’t want to feel like it was only me. If I couldn’t land a pitch at Rolling Stone or Pitchfork, I was going to do something I could take ownership of.

I made of list of some of my favorite writers at the time, and thought I would reach out and interview these writers, post the interviews on my website. I’ll do a dozen, one a month, make it a personal column and see what happens. 20 turned into 30, then over 50. I never posted any of them on my website.

How did you approach them? What did you say they were going to do with their responses? What did your email say?

“In an attempt to keep myself creatively fulfilled in between assignments (I start to get really stir-crazy when I can’t think of a good pitch), I’ve taken it upon myself to start my own personal interview series for my website blog, talking not with musicians, but music journalists, hoping to discuss everything from their influences as writers, their own life and work, to the industries of music and the media and their relationship together. I want to showcase and acknowledge the professionals I’ve come to look up to and admire, and hopefully learn something from the experience. My ultimate wish, given the time and willing participants, is to turn these conversations into an oral history of some kind, documenting music journalism’s evolution parallel to popular music itself. Having begun the project with the amazing Amanda Petrusich, I’d like to keep the ball rolling with you if you’d be interested. I’ve been a big fan of your work for some time, and feel it would be a true privilege to speak with you. Let me know what you think.”

The example I gave them to look at was Judd Apatow’s Sick in the Head: Conversations About Life and Comedy. When he was a kid he just started interviewing all of his comedy heroes and eventually he published them into a book.

I quickly found out the only thing music journalists like taking about more than music, is music journalism.

What was your criteria for who ended up in the book?

I started with my favorites, people I read a lot, people whose work I really admired. When I reached out to Jessica Hopper, she told she would be interviewed on one condition: I needed to diversify. When I reached out via email to make my case, or plea, as it was, I would include the updated list of writers I had gotten to participate, as a way of legitimizing the whole thing. When Jessica saw the list, she saw the problem: white men, a few white women. I knew this was a problem so I asked her for help. She gave me a list. I started reading the works of these writers covering artists and writing on topics that were completely out of my normal reading habits. It opened up a whole new world for me. That was one of the best parts of working on this book, being exposed to writers that I probably wouldn’t have sought out or gotten to experience if I stayed in my little privileged, straight white male bubble.

That is one of the things that stands out in the book. So many of them said they were from immigrant families, but even with that distinction, how their stories were really similar to non-immigrant journalists.

Yes! How it informed what they listened to and how that evolved as they came to form their own identities. The music always came first, and from that comes this need to understand it, to make sense of it.

How were the interviews conducted?

They were all over the phone. Jack Rabid [of The Big Takeover magazine] was the only exception—we video chatted. Journalists keep crazy schedules, so finding time to chat was always a challenge. Some were as short as half an hour. Some lasted two hours or longer. There were some interviews I ultimately decided not to include. They were just conversations. There weren’t any multi-part interviews. Whatever someone said all came from a single conversation. I made a point to let the conversations go where they would naturally. The biggest point of divergence in the questions occurred when I knew someone was more of a critic or essayist and when someone was a feature writer or profiler. There was always the rare unicorn that was skilled at both criticism and interviews.

Did books like How to Write About Music by Marc Woodworth and Ally-Jane Grossan have any impact on your book?

How to Write About Music was HUGE. I love the 33 1/3 series That’s how this really got started in earnest. Before writing this book I really wanted to write a 33 1/3 book. I worked on and submitted a proposal. The particular year I submitted, there were maybe 400 entries and I got shortlisted to the top 100, which was a huge ego boost for me. While I ultimately didn’t make the final cut, it got me thinking about wanting to really pursue something. My favorite part about How to Write About Music were all the testimonials tucked in each chapter. I thought to myself, “I’m going to make a book of just that.”

Were there other books that had an impact on your approach to your book?

Marc Maron’s Waiting for the Punch. It is a simple collection of interviews from his podcast. The chapters are all divided by topic: fame. sexuality, identity, fear, sex and love, mortality, mental health.

That is what the book is like, not so much you writing as editing the quotes where there is a flow between different journalists’ ideas and points.

That was my favorite working element of the book, taking all these quotes I had assembled and putting them together in some sort of order. This gigantic puzzle piece by piece.

How did it evolve from the initial idea of an interview series on your site into being a book?

I was using the website thing as an on-ramp to make it seem less daunting. I didn’t start writing the book proposal until 50 interviews in. I didn’t do this book the way you’re supposed to write a non-fiction book. Fiction books are the ones you write completely and then try to sell it. Non-fiction you write a little, get a sample and develop a proposal, get a publisher, and then write the book. I didn’t do that, which was probably why writing and submitting proposals was the most nerve-wracking part of the whole thing.

What was the book proposal process like? Did you have an agent?

No one teaches you how to get a book published. I had a few resources, a bible of how to write a proposal that really helped me. But the type of book I had developed didn’t exactly scream: “Mass market.” There were a lot of rejection letters from agents. But then I found out if you submit a proposal to an academic press, they usually specialize in weird niche subject matter, you don’t need an agent. The proposal goes straight to the publisher and that’s how I wound up at UMass Press. It’s a miracle this book got published. They were the only ones that responded. It’s not like I was fighting publishers off vying to publish my book, but my editor really liked the idea, and that was enough for me.

You said in the book, “I like to think of this book as a kind of massive roundtable discussion.” Who do you envision the book’s audience to be? It’s very niche.

New music journalists.

Is this book your solution to not being able to land a music writing job?

It was a way of taking control. I am medically diagnosed with OCD—not, “Oh I’m so OCD because I like things neat.” Real OCD. A lot of the stress and frustration that invades my life comes my inability to exert control over it. I felt like a failure for a long time, particularly in my marriage. I met my wife first week freshman year of college. We’ve been together ever since. For over a decade she was the anchor that made our life financially livable. As a spouse, there’s a lot of guilt that comes with that. Panic attacks were fairly common.

I interviewed for editorial assistant job for Virginia Living Magazine, and I got the job. I told my folks. I told everyone. I was finally, getting an editorial writing gig for a publication. After their initial salary offer I was encouraged to negotiate with a higher offer, and they would offer me something that would compromise in the middle. After I sent in my salary negotiation they rescinded the offer. I was crushed, not because I lost the job, but because I felt like I was finally going to stop feeling like dead weight. This month I celebrated the five-year anniversary of my first actual job as a writer and editor for the American Medical Group Association. The reason I got that job, my boss believed that if you could write one thing you could write about anything. It helped that in his youth when he lived and worked in NYC he wrote for Rolling Stone.

Going full circle back to the book’s introduction, you say that once you made the connection with other music journalists, you couldn’t help but compare yourself to them. This is such a double-edged sword.

It was a huge thing. There were a few moments working on this book I got really depressed realizing, “These guys are pulling off doing the things you have always wanted to do.” The whole endeavor could have turned on me. I was listening to an entertainment interview podcast where these two celebrities were talking about this exact same thing: imposter syndrome, the feeling of inadequacy to their peers. One of the points made during the conversation is that the world is so big. Back in the day you were just part of a tribe, a community. If you were a blacksmith, you were the best blacksmith for hundreds of miles, if you were a seamstress you were the best seamstress for that tribe. That gave you a sense of purpose and value in that community. But now, the tribe is immeasurable. How do you measure your value? In this conversation one of the guys said, “I can’t compare myself to others. It’s a futile undertaking. All I can do is compare myself to who I was, who I had been, and look at how I have personally grown in my profession, how I have grown as a person.” That really saved me. I am not going to be Rob Sheffield, Chuck Klosterman, Amanda Petrusich, or anyone else. I can only be who I am, and do the best work that I can in a given moment.

Support Under the Radar on Patreon.

Most Recent

- Fontaines D.C. Announce New Album, Share Video for New Song “Starburster” (News) — Fontaines D.C.

- Yannis Philippakis of Foals Announces New EP with the Late Tony Allen, Shares “Walk Through Fire” (News) — Yannis & The Yaw, Foals, Tony Allen

- Premiere: Meli Levi Shares New Single “Close to You” (News) — Meli Levi

- Hana Vu Shares New Song “22” (News) — Hana Vu

- John Grant Shares Lyric Video for New Song “The Child Catcher” (News) — John Grant

Comments

Submit your comment

There are no comments for this entry yet.